S & H Green Stamps

S & H stood for the Sperry and Hutchinson Company, which began in 1896. There were several saving stamp companies. Top Value and Gold Bond stamps were also popular.

Jim Cherry School of Brookhaven

Jim Cherry Elementary School, at 3007 Hermance Drive was built in 1950 and designed by Wilfred J. Gregson, of Gregson and Ellis Architects. Today the school is DeKalb PATH Academy in Brookhaven.

Oak Grove School, 1916 and 1927

Oak Grove School of DeKalb County is included in the 1916 book, “Educational Surveys of DeKalb County and Union County, Georgia.” Each school has a photo and a general description of the school grounds, building and teachers (or teacher).

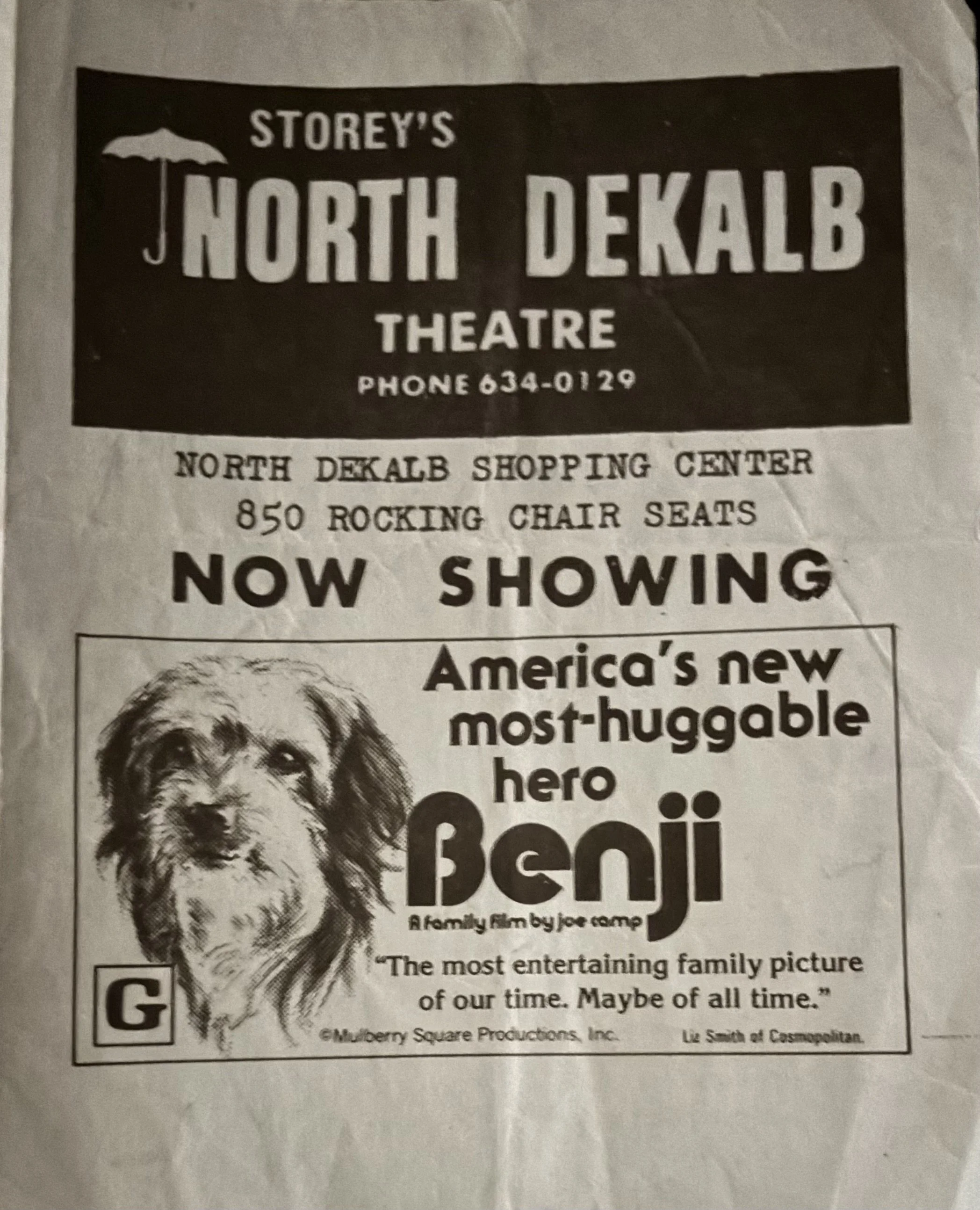

Storey’s North DeKalb Theatre

Storey’s North DeKalb first opened as a single theatre in 1965. “Lord Jim,” starring Peter O’Toole, was the first film to run at North DeKalb. By 1976, the theater was changed over to a twin, by dividing the existing theater down the middle. This created two narrow theaters, each with a smaller screen.

Blanton House in Chamblee

According to a 1987 article in the Atlanta Journal, the house was built in 1917.

Chamblee dairies video

Shannon Wiggins, Public Relations and Communications Director for the city of Chamblee, contacted me to give a brief talk on the history of Chamblee dairies.

Early Georgia teachers trained at “Normal Schools”

Early schoolteachers in Georgia often received their training at what was known as Normal School. Normal Schools were established in Georgia towards the end of the 19th century to prepare teachers to teach elementary aged students. It was usually a two-year program and the term normal referred to establishing clear standards or “norms” for public schools.

Tragic 1929 explosion at Stone Mountain rock quarry

The March 1, 1929 Atlanta Constitution reported that an explosion at Stone Mountain near the Confederate carving killed seven men and injured six. These numbers may have increased as the days passed. The men were all working for Stone Mountain Granite Corporation.